Tapping the Scales of Justice - A Dose of Connecticut Legal History

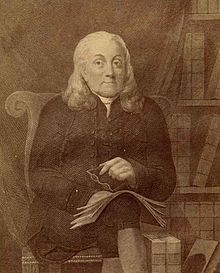

The Litchfield Law School, the first of its kind in the United States,

was founded by Tapping Reeve in 1784. The custom for students of law in the

18th century was to be tutored privately or serve under apprenticeships.

Tapping Reeve, after being admitted to the bar, began teaching individuals

in his living room. His first student was his brother-in-law, Aaron Burr.

Eventually, Reeve constructed a school building next to his home to

accommodate growing enrollment. He operated the school by himself until

1798, when he was appointed as a Superior Court judge. He then invited a

partner, James Gould, to join him at the school. Together, they developed

an eighteen month course of lectures based on a system of legal principles

and different subject areas of legal practice. Reeve also established

student moot courts. More than 1,100 students attended the school from every

region of the new United States of America before the school closed in 1833.

Tapping Reeve, after being admitted to the bar, began teaching individuals

in his living room. His first student was his brother-in-law, Aaron Burr.

Eventually, Reeve constructed a school building next to his home to

accommodate growing enrollment. He operated the school by himself until

1798, when he was appointed as a Superior Court judge. He then invited a

partner, James Gould, to join him at the school. Together, they developed

an eighteen month course of lectures based on a system of legal principles

and different subject areas of legal practice. Reeve also established

student moot courts. More than 1,100 students attended the school from every

region of the new United States of America before the school closed in 1833.

Distinguished alumni of the school included two Vice Presidents of the

United States (Aaron Burr and John C. Calhoun), as well as twenty-eight

Senators, one hundred one Congressmen, six Cabinet Ministers, fourteen

Governors, and three Justices of the United States Supreme Court. Thirteen

graduates served as state Supreme Court Chief Justices. In 1966, the

Department of the Interior designated the school as the first law school in

the United States. A compilation of the names of

Litchfield Law School Students who attended the school is available on

the web site of the Litchfield Historical Society. The

Tapping Reeve House and Litchfield Law School still stand and are

operated by the

Litchfield

Historical Society. Visitors may tour the site in Litchfield,

Connecticut, from mid-April through November. Admission is free.

In 1814, Tapping Reeve was elevated to Chief Judge of the Connecticut Supreme Court of Errors. Many of

his decisions can be reviewed in early Connecticut Reports volumes. He

frequently wrote decisions as if he were lecturing a classroom of his

students, asking rhetorical questions and then answering them. He also often

reached back to English law for authority or for an analogy when writing

opinions. Here is what he had to say in a case involving trespass:

"suppose that the lord of a manor should sell a highway through his manor...

no deed to any person of the land covered by the highway being executed...

what would pass to the public by the sale... Nothing but a right of passage

for the king and his subjects; and all the rest would remain the property of

the lord of the manor as long as the highway continued to be a highway..."

[See page 105 of 1 Conn. 103 (1814)]

For further reading on Tapping Reeve and the Litchfield Law School:

2 Conn. Bar J. 72, 19 Conn. Bar J. 245, and 40 Conn. Bar J. 440

Librarians at the Yale Law School Lillian Goldman Law Library have completed a digitization of 143 notebooks

kept by students of the Litchfield Law School. The

Litchfield Law School

Notebooks and the

Litchfield Law School Sources are available online to the public through

the open access portal eYLS and the

Yale Law School Legal

Scholarship Repository.

Doses of Connecticut Legal History